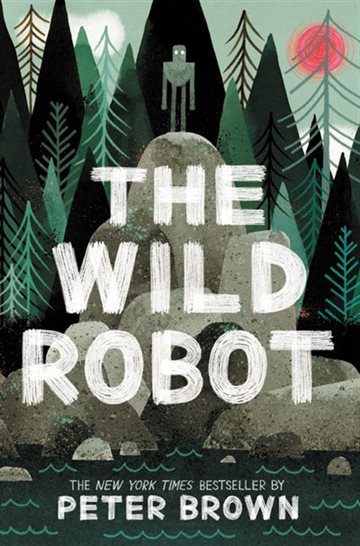

“‘You have also taught me to be wild,’ said the robot. ‘So let us all celebrate life and wildness, together!'”

— The Wild Robot, Peter Brown

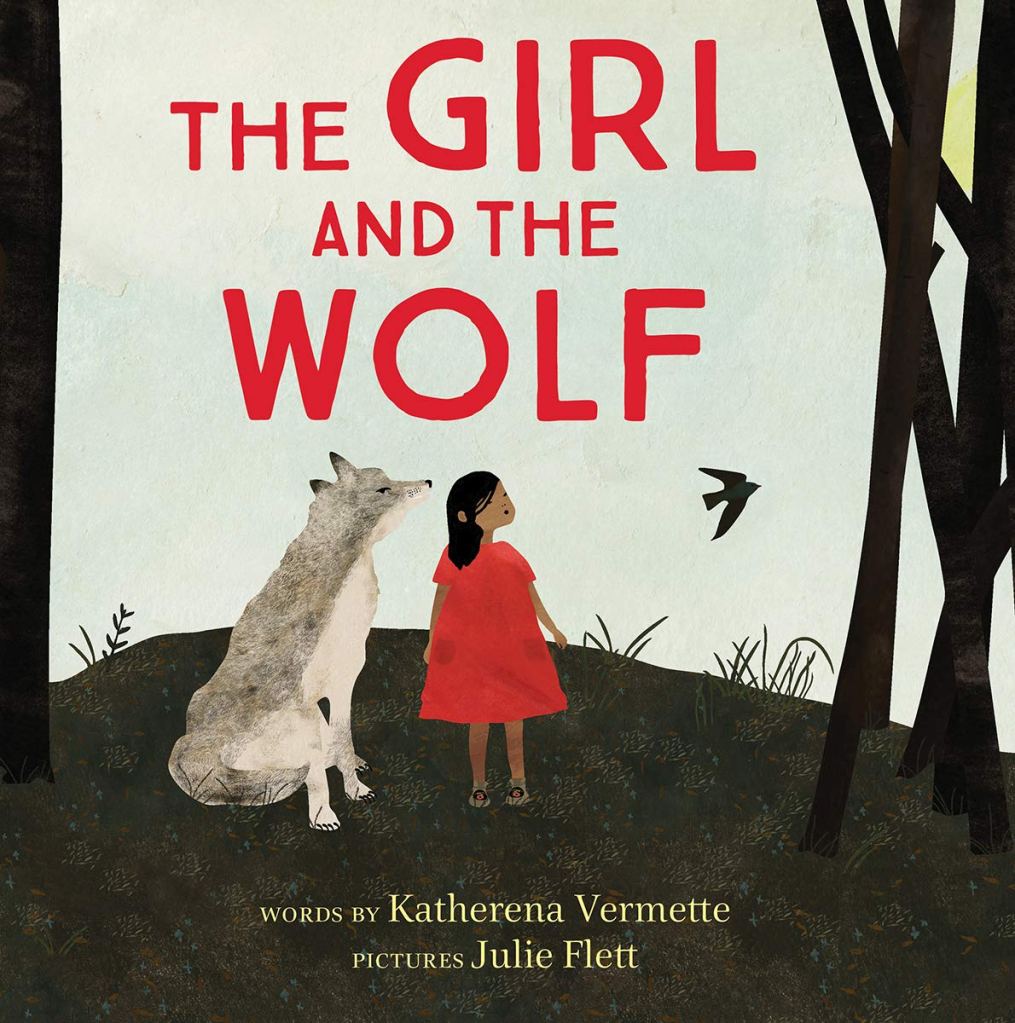

The Girl and the Wolf, a short story written by Katherena Vermette and illustrated by Julie Flett, seems to take a twist on the classically known story of Little Red Riding Hood. The story features an Indigenous girl who gets lost in the woods while out with her mother. In the woods, she meets a wolf; but instead of the wolf following her to granny’s house and eating the girl, the wolf helps guide the girl back to her mother. He reminds her of her own abilities to survive and find her way back home to her mother.

Similar in theme, The Wild Robot, a novel written and illustrated by Peter Brown, is about a robot named ROZZUM unit 7134 (but you may call her Roz), who ends up on an island after a hurricane crashes her ship. The robot must adapt to her unfamiliar surroundings and learn from the animals inhabiting the island in order to survive. At first, this is difficult for Roz, who appears to be a shiny and scary monster to the animals on the island, who greet her with hostility and fear. Over time, though, Roz begins to pick up a thing or two that will help her survive, and she begins to make friends with the locals.

What I enjoyed about both of these books is that they are both relatable to a large audience of readers. Though Vermette and Brown’s books are fictitious and a bit fantastical (as we all know wolves don’t talk and robots don’t just randomly end up stranded on islands in real life), the feelings they depict in their books—of feeling lost, survival, building trust—are all universal experiences we can all relate to on an emotional level.

Brown does an exceptional job of this in his novel, which delves deeper into the experiences many minority communities often face: fear of exclusion, being viewed by others as a “monster” for being different, learning a new language, and the uncertainty of how to make friends in a new culture.

“Roz wandered the island, covered in dirt and green growing things, and everywhere she went, she heard unfriendly words. The words would have made most creatures quite sad, but as you know, robots don’t feel emotions, and in these moments that was probably for the best.”

–The Wild Robot, p. 53

All the animals were scared of Roz in the beginning, calling her a monster, simply because she was new and different and at first didn’t know the language of the animals. This is not unlike the treatment of immigrants from the Latinx community (or people who simply look like immigrants) in the United States right now. Fear of the unknown is a common theme worldwide and though not explicitly stated, Brown does an excellent job of alluding to this fear throughout his novel.

Another theme that arose in The Wild Robot was that of motherhood—or even parenthood in general. Roz saves and adopts a gosling she names Brightbill, whose family was killed in an accident on the island, and struggles with the new responsibility of parenting—an unusual thing for a robot to do. She seeks help from one of the older geese on the island, Loudwing, to help the little gosling survive. Loudwing tells Roz that she must now act as the gosling’s mother, and gives her many helpful rules for being a mother:

“‘Yes, I do want him to survive,’ said the robot. ‘But I do not know how to act like a mother.’

‘Oh, it’s nothing, you just have to provide the gosling with food and water and shelter, make him feel loved but don’t pamper him too much, keep him away from danger, and make sure he learned to walk and talk and swim and fly and get along with others and look after himself. And that’s really all there is to motherhood!'”

–The Wild Robot, p. 75

I had to laugh after reading this paragraph, especially at that last sentence, “And that’s really all there is to motherhood!” To sum up motherhood in such a neat little box seems to not capture it fully; but at the same time reading this section details just how much that mothers really do for their children! I also appreciated that in this listing of motherly qualifications, the goose did not mention the need to give birth to be a mother; this is often a quality that is brought up a lot in the defining of what it is to be a mother, but it is not a true qualifier like the other things listed by Loudwing. The discussion between Roz and her son Brightbill on page 125 summarizes this struggle many families with adopted children often experience at some point or another:

“Parents. The word suddenly left Brightbill feeling uneasy. ‘You’re not my real mother, are you?’

‘There are many kinds of mothers,’ said the robot. ‘Some mothers spend their whole lives caring for their young. Some lay eggs and immediately abandon them. Some care for the offspring of other mothers. I have tried to act like your mother, but no, I am not your birth mother.'”

–The Wild Robot

Being adopted can sometimes feel to the child like betrayal, abandonment, and unbelonging; in reality, though, it is the opposite. Being adopted is and should be a celebration of the wanting of a child by adoptive parents, and the love in adopted families is often stronger than some families based on blood relation. Reading this—especially knowing that this conversation between Roz and Brightbill was in response to Brightbill being teased for who is mother was—made me consider the reality of this teasing that is often experienced by both parents and children of LGBTQ+ families alike. This is another group that is oppressed for being different or out of the “norm” that society has built, and is sadly often one that is labeled as monstrous.

“‘Stay away from my mama!’ Brightbill swopped down and skidded to a stop between the robot and the bears.

‘So the rumors are true!’ Nettle laughed. ‘There really is a runty gosling who thinks the robot is his mother! How could anyone be so stupid! Do yourself a favor, gosling, and fly away before you get hurt!'”

–The Wild Robot, p. 140-141

This harsh jab by a young bear toward Brightbill is a direct reflection, in my eyes, of the cruelty too often received by members of the LGBTQ+ community and their children: the insinuation that these families are not “real” families because they do not line up with the nuclear family expected by society. The young bears learn their lesson later, however, when Roz saves one of them and get a talking to from Mother Bear. It is important to remember that this does not always happen in real life, as children’s perspectives on matters like these generally originate from the views of their parents.

In both books, it is the characters that, in the real world, are often put down and frowned upon—a brown-skinned girl and a “monster”—that develop their own agency the most fully. In The Girl and the Wolf, the wolf helps the girl to acquire this agency; when he finds her lost in the woods, rather than taking advantage of her situation or telling her exactly how to get back, the wolf simply asks her, “What are you going to do?” Each time, the girl responds by saying she doesn’t know, but the wolf reminds her, “Yes you do,” and refers her to use her own senses to get her back home.

In The Wild Robot, Roz develops agency out of necessity for survival. As she adapts more and more to her environment and becomes more “wild,” the robot begins to have influence with her friends, who look up to her. She uses this agency to take action to help her community: building homes and fires to keep the animals of the island warm during a terrible winter, throwing a celebration for the island, and in the end, doing what she knows is best for herself and those she loves.

What makes for a good book?

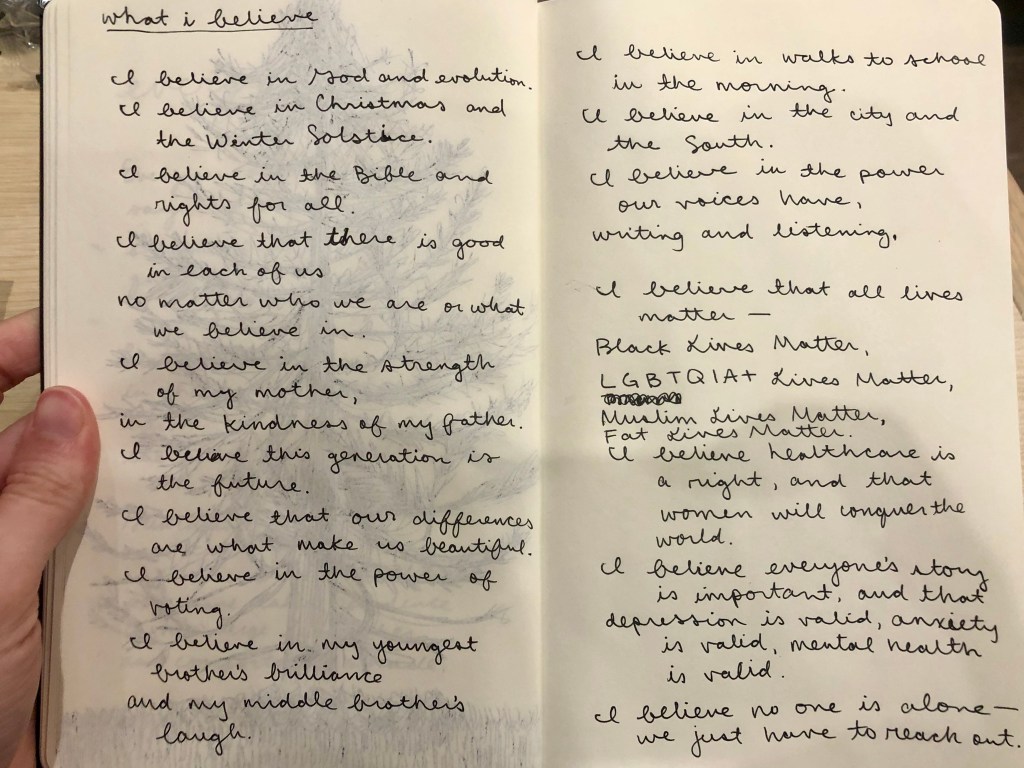

Prior to reading these books, I wrote down a few characteristics that I believed to qualify a good book. This is what I wrote:

I would say a good children’s book is colorful, whether through pictures or words, and instills vivid imagery in the mind of the reader. It would have a moral or learning experience for the child which helps them remember the book and incorporate the lesson in their own lives. It is generally “cute” and a display of loving others. Good children’s books are loved by children and adults alike because of its good storytelling. Finally, they are also inclusive of people who are unique or different from us (or show value placed on people not generally seen in mainstream literature); this inclusion may also be featured through the author or illustrator.

Both The Girl and the Wolf and The Wild Robot reflect these criteria I have come up with. The Girl and the Wolf‘s illustrator Julie Flett uses collage to create colorful and visually-stimulating pictures on each page. The detailed descriptions in The Wild Robot create vivid images in the mind of the reader, not to mention the sweet illustrations throughout the novel. The Girl and the Wolf and The Wild Robot alike have multiple learning experiences, both discussed in detail throughout this post and in the section below; inclusivity are large themes in both books as well. Both these books are also beloved by children and adults alike.

How can I apply lessons from these books to my own classroom?

Something that is always needed in classrooms across the country: more children’s books that show students their own agency and power to change their destiny, especially through the lives of girls. Often these books that inspire “girl power” are bright, colorful, and feature girls doing remarkable things. I like that The Girl and the Wolf is one of these “girl power” books without the sparkle and flash of most of the other books in this category; the girl doesn’t break any societal barriers, but her experience is instead far more relatable to the everyday reader. In a stressful situation, she takes in her surroundings, takes advice from others, and gets herself out of trouble all on her own. This book also serves as an example of children’s literature featuring a girl from an Indigenous peoples group that is not all about traditional celebrations or practices of Indigenous communities. While it is good these books exist, it is also important to show other realms of life for Indigenous peoples as well, to show a more holistic viewpoint and steer away from stereotypes and single stories.

Because The Wild Robot is a longer read than The Girl and the Wolf, there are many more themes that can be addressed with children in your classroom as you read. It functions as a pathway to many critical discussions about topics such as inclusivity, diverse families, making a positive impact on your community, and even climate change (see section where the island inhabitants discuss the ever-hotter summers and the ever-colder winters, p. 191-192). All of the conversations that arise while reading The Wild Robot are important to have in your classroom; ask students how they think what they are reading relates to the world around them, to be empathetic toward characters in the story, and to think critically about each of these themes discussed in this post.

So what are you waiting for? Go read The Girl and the Wolf and The Wild Robot now!

References

Brown, P. (2016). The wild robot. New York ; Boston, NY: Little, Brown and Company.

Sharp, C. (2018, May/June). Readers can do anything: Our children's literature day lunch keynote on the transformative impact of a good book. Literacy Today, 35(6), 40-41. Retrieved from http://literacyworldwide.org

Short, K. G. (2012). Story as world making. Language Arts, 90(1), 9-17.

Vermette, K. (2019). The girl and the wolf. Canada: Theytus Books. References