“When you fight for justice, others will follow.”

–Separate is Never Equal, Duncan Tonatiuh

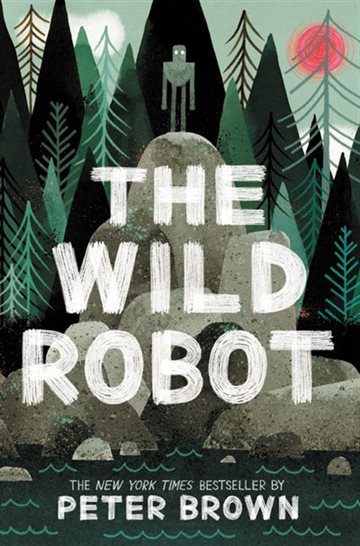

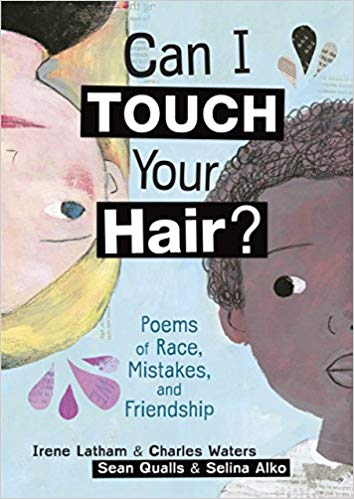

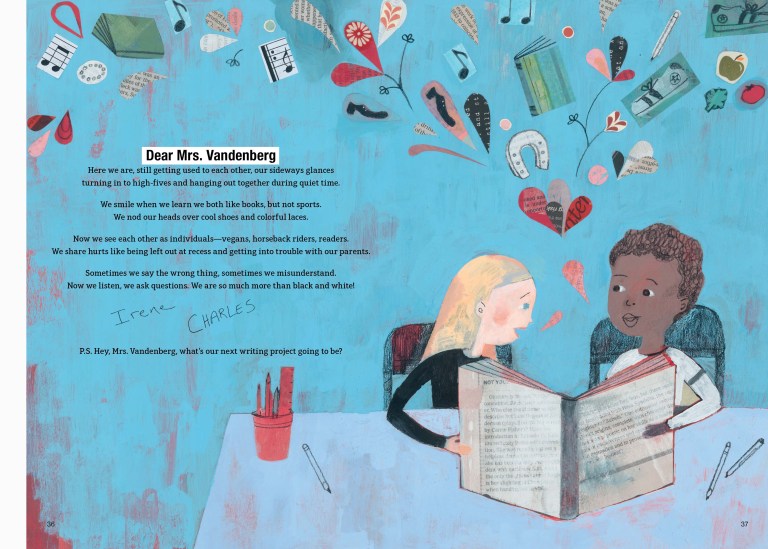

Can I TOUCH Your Hair? Poems of Race, Mistakes, and Friendship, written in 2018 by Irene Latham and Charles Waters and illustrated by Sean Qualls and Selina Alko, follows fifth-grade versions of Irene, who is White, and Charles, who is Black, in a contemporary elementary school. When the two get paired together for a poetry project in class, both seem unexcited, to say the least: “Charles is the only one left. … Now I’m stuck with Irene?” (p. 4-5). But the two, who at first do not know each other too well, find some surface-level commonalities to write about as a starting point—shoes, hair, school, church. Eventually, they find they have even more in common—feelings of being left out, a range of emotions about things heard on the news, being punished by parents, methods for handling fear, and a love of reading. “Sometimes we say the wrong thing, sometimes we misunderstand. Now we listen, we ask questions. We are so much more than black and white!” (Latham & Waters, p. 36). Written completely in prose, Latham and Waters, complemented by Qualls and Alko, beautifully and eloquently demonstrate how children think about race, identity, and friendships.

Can I TOUCH Your Hair? was written by a Black author and a White author, and illustrated by a Black illustrator and a White illustrator. These pairings serve to better capture the experience that the book hopes to accomplish: how do we view one another from a racial standpoint and how do we come together to create something beautiful? Often, when it comes to racial discussions, we are encouraged to not bring it up with children for fear of students being confused or too immature; however, children know much more than we tend to think they do. Students need to be able to “reflect on both their personal knowledge or experiences with racism in today’s America and … the history of civil rights and the current state of the movement” (Smith-Buster, p. 110). This book is an excellent starter to begin to have those conversations with students and to allow them to do such reflection. According to the author and illustrator bios on the book jacket, Latham and Waters “believe poetry can start conversations and change lives. With a little courage and understanding, together we can make the world a better place” (2018). I couldn’t agree more!

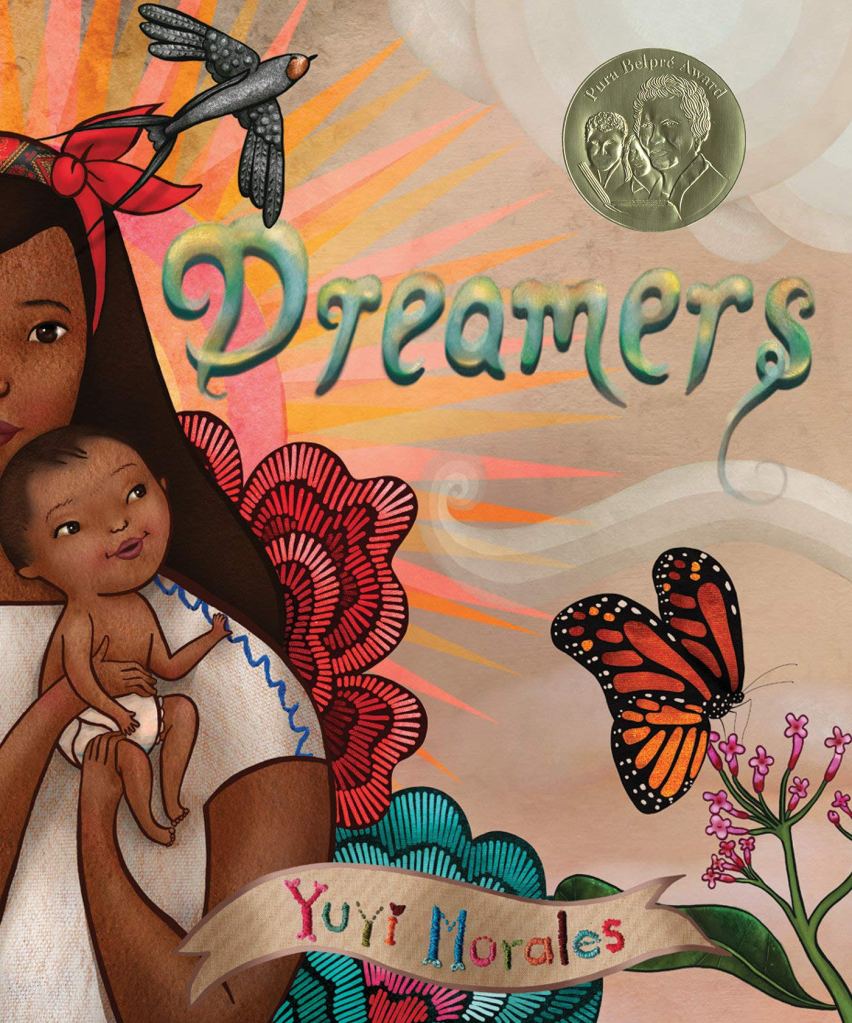

Duncan Tonatiuh’s biography, Separate is Never Equal: Sylvia Mendez & Her Family’s Fight for Desegregation (2014) recognizes the landmark desegregation case of 1946 Mendez v. Westminster that took place seven years before Brown v. Board of Education. A Mexican author, Tonatiuh writes from the perspective of a Mexican-American girl Sylvia Mendez, who at the time of the case was just eight years old, as she struggles with the racism and inequality of being denied public education in the “white” school. Eventually, with the hard work of Sylvia’s family, a good lawyer, and the help of the community, the state of California deems this to be unconstitutional and all public schools must become integrated. As an adult, Sylvia is now an American civil rights activist who continues to share her family’s story and fight for school integration. Separate is Never Equal is now a Pura Belpré honor book for its success in portraying, affirming, and celebrating the Latinx cultural experience in an outstanding work of literature for children and youth. Please enjoy the video below which features an interview with the author/illustrator Duncan Tonatiuh!

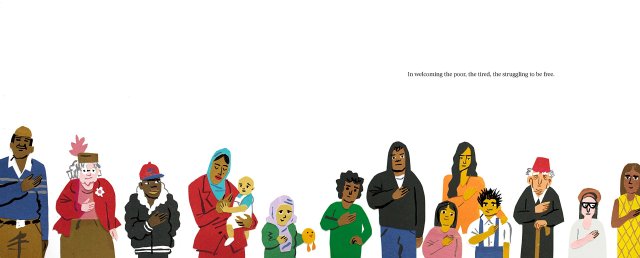

Critical race theory (CRT) suggests that “racism is mundane and everywhere rather than aberrant and sporadic … the majority of racism remains hidden beneath a veneer of normality and it is only the more crude and obvious forms of racism that are seen as problematic by most people” (Marshall, p. 79). Hidden under that “veneer of normality” includes children’s picture books, which too often present “implicit and explicit misrepresentations about Indigenous peoples and people of color that, because of their repetition across time and media, seem unremarkable” (Marshall, p. 79-80). To combat this mundane racism found in children’s books, Tonatiuh, Latham, Waters, and other contemporary authors use counter-storytelling to tell the stories of people, including people of color, whose experiences are often untold or misrepresented, and to expose and challenge the majoritarian stories of racial privilege (Marshall, p. 80).

For example, Latham and Waters use Can I TOUCH Your Hair? as a counter-narrative that represents authentic voices to critique dominant cultural assumptions. Both Irene’s and Charles’ portrayals in the book serve to challenge and dismantle stereotypes: Charles excels at writing, Irene “begged for an Afro” when she was little (p. 8), Charles is bad at basketball but “words gush out of [his] mouth, smooth and fast like the River Jordan” (p. 14), Irene wants to play freeze dance with the Black girls at school. All of these things counter the stereotypes surrounding both Black and White people, specifically Charles. Charles is supposed to make bad grades, play video games, say things like, “You ain’t,” or “You is,” or “I’m doing good” (p. 22), and is even asked by a White student why he “always [tries] to act like one of [them]” (p. 22), as if acting in certain ways is what makes a person Black or White.

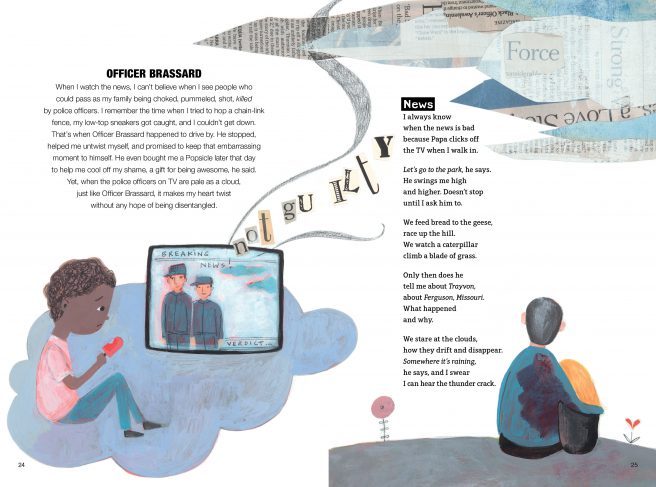

The book also counters the idea I discussed above that children do not or cannot understand themes about race. In poems like “Church,” “Sunday Service,” “Forgiveness,” “Apology,” “Officer Brassard,” and “News,” it is obvious that children do, in fact, understand issues surrounding race, racism, and racial inequalities. In an interview by Libby Stille (2018), Waters said, “Irene’s poem “News” is [his] favorite of the book. She wrote about police brutality with such sensitivity, [he] tried [his] hardest to match that depth of feeling in [his] response poem, ‘Officer Brassard.'” The two poems mentioned by Waters (see above, p. 24-25), illustrate the thoughts and feelings children might have about the horrible things on the news such as police brutality, specifically toward Black people. The contrast between Charles’ poem and Irene’s poem help readers understand the different ways we understand violence and injustice through our own racial lens.

Separate is Never Equal also serves to use counter-storytelling as a tool for analyzing racial privilege through a CRT lens. In her article, “Counter-Storytelling through Graphic Life Writing” (2016), Elizabeth Marshall uses the term “graphic life writing to refer to the construction of a life story through image and text in forms such as the picture book or comics” (p. 79). She continues to say that, “Graphic life writing represents one way to deepen an understanding of school as an institution with a history that continues to segregate and exclude youth because of their ethnic and/or racial backgrounds” (p. 80). In her article, Marshall examines the ways in which Tonatiuh’s illustrations provide a counter-narrative for people of color in the United States.

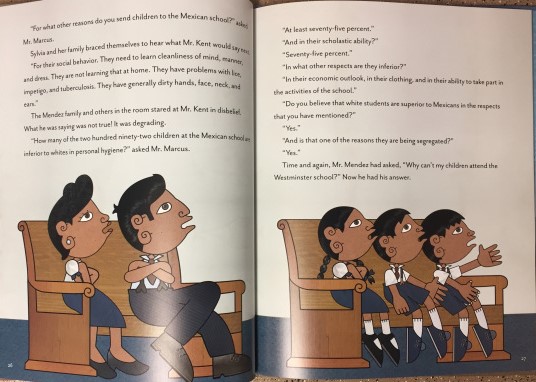

On pages 26-27, the lawyer representing the Mendez family, Mr. David Marcus, asks one of the superintendents who sent the Mendez children to the Mexican school, Mr. Kent, why? Mr. Kent claims that he did so because the Mendez children “need to learn cleanliness of mind, manner, and dress,” calling them dirty, unintelligent, and generally inferior to the White children attending the school. Tonatiuh’s illustrations depict the Mendez family’s shock and outrage at Mr. Kent’s racist words: both parents and Sylvia’s arms are crossed, Sylvia’s brothers put their arms up in frustration, and all mouths hang open in disbelief. “Time and again, Mr. Mendez had asked, ‘Why can’t my children attend the Westminster school?’ Now he had his answer” (p. 27). That answer was based upon the systemic White supremacist ideas that White people are inherently better than people of color. It is important to note, however, that people of color do present difficulty “in their economic outlook, in their clothing, and in their ability to take part in the activities of the school” (p. 27) because they are not welcomed into the school with better resources; this creates a never-ending loop of feelings of inferiority and of supremacy for people of color and White people respectively.

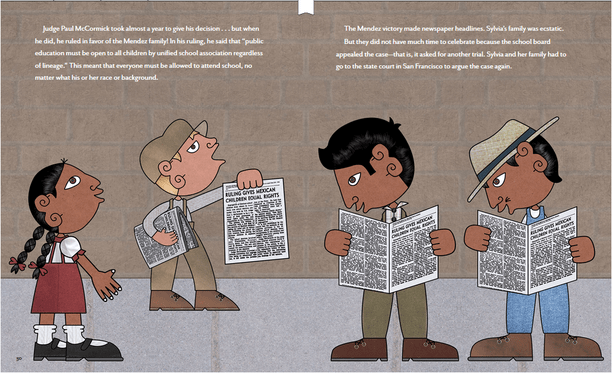

Tonatiuh confronts the racism and stereotypes presented by Mr. Kent in another double spread on pages 30-31, which illustrate the Mendez victory celebrated in the newspapers. Sylvia is depicted as “ecstatic,” with a smile on her face and her hands uncrossed and extending outward. The spread shows people reading the newspaper that was published saying, “RULING GIVES MEXICAN CHILDREN EQUAL RIGHTS.” This positions the reader to recognize and refute racism and show the activism from Mr. Marcus and the Mendez family in combating the racist ways of the school districts involved, by showing students the power they have through community and civil activism to make a change in their world.

How can I apply lessons from these books to my own classroom?

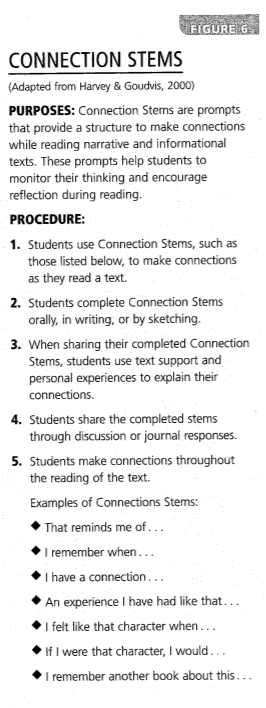

These books provide platforms for opening up critical conversations about discrimination, overcoming obstacles and injustices, disrupting stereotypes, and fostering positive conversations about race and identity with students. We must remind students that these injustices surrounding racial identities are still occurring today, whether it be the “unofficial segregation” Tonatiuh mentions in his Author’s Note (p. 36) or the Black Lives Matter movement alluded to in Can I TOUCH Your Hair? (p. 24-25). A good starting point for opening up these critical conversations could be by examining the list of guiding questions adapted from Yosso’s (2005) framework referenced in Marshall’s (2016) article:

- How does the subject of this auto/biography maintain hopes and dreams in the face of barriers?

- How do the illustrator and/or author communicate their story in images and words?

- Does the author include or write in more than one language or dialect? Are certain literary forms used in the book, such as parables or poems?

- What knowledge or lessons do young people in these auto/biographies use that come from their families and/or communities?

- What documents, photos, or information do the author and/or illustrator include in their life writing? Why?

- Upon what networks of people in the community do the author and/or illustrator rely?

- How do youth navigate through institutions like the school that are not set up for communities of color and/or Indigenous peoples?

- In what ways (e.g., challenging adults, participating in protests, testifying in court) do youth resist unfair treatment or discrimination?

With all this in mind, remember what Latham and Waters say: “With a little courage and understanding, together we can make the world a better place.”

References

Hinz, C. (2018, March). Writing, editing, and sharing poetry from can I touch your hair?. Interview by L. Stille. Retrieved from https://lernerbooks.blog/2018/03/can-i-touch-your-hair-irene-latham-charles-waters-carol-hinz.html

Latham, I., & Waters, C. (2018). Can I touch your hair? Poems of race, mistakes, and friendship. Minneapolis, MN: Carolrhoda Books.

Marshall, E. (2016). Counter-storytelling through graphic life writing. Language Arts, 94(2), 79-90.

Smith-Buster, E. (2016). Social justice literature and writing: The case for widening our mentor texts. Language Arts, 94(2), 108-111.

Texas Bluebonnet Award. (2015, February 15). Separate is never equal Duncan Tonatiuh [Video file]. Retrieved from https://youtu.be/n7-kzJVcOUw

Tonatiuh, D. (2014). Separate is never equal: Sylvia Mendez and her family's fight for desegregation. New York, NY: Abrams Books for Young Readers.