“Maybe, I am thinking, there is something hidden

like this, in all of us. A small gift from the universe

waiting to be discovered.”

–“hope onstage,” brown girl dreaming, Jacqueline Woodson

As I struggled to figure out how to start this blog post, falling into the same question Calkins (2006) refers to students asking, “where do I start?,” I began thinking back on a short essay I wrote in a theatre class my sophomore year of college, called My Creative Process: Rituals of Preparation. I started off this essay with the words: “Right now I am thinking about what the best way to start this essay is.” It’s funny how, even with so much practice writing, my process of unknowing how to start remains the same. Luckily for me, in the span of my almost 20 years of writing practice, I’ve gained a few tricks up my sleeve for getting started and creating a lead to “grab, pull, or yank” (Calkins, 2006) my readers into my stories: such as starting off a story with an anecdote that takes the reader into the past, just like this post!

Lester Laminack, in his foreword to Stacey Shubitz’s book, Craft Moves: Lesson Sets for Teaching Writing with Mentor Texts (2016), states that “basically anything in print can be studied closely—using a lens for ‘How and why did they do that?’—to extend your repertoire of craft moves” (p. viii). Young writers need to study text in many forms, to build up those craft moves or “tricks up their sleeve.” As Dorfman and Cappelli put it in Mentor Texts: Teaching Writing Through Children’s Literature, K-6 (2007), “Mentor texts provide road maps for students to follow” (p. 124). I use mentor texts to this day to imitate writing and use strategies of professional authors to improve my own writing all the time.

But what makes a story good? Readers want to be pulled in with the lead of the story, “the first sentence, the first paragraph, or the first several paragraphs that begin the story” (Dorfman & Cappelli, 2007, p. 107). Some readers decide after reading the very first page of a story whether they want to continue or not; some flip to the back of the book to determine if it’s worth their investment. Dorfman and Cappelli discuss how too often, students don’t know how to control time in their writing—they start with too much time before the main event, they expand the story over too much time, or they can’t tell where the story should end.

To begin to show students how they can explode a small moment or span a larger period of time through focusing on one essential moment to the next, students should internalize the use of the traditional beginning, middle, and end of a story. Chapter 5 of Craft Moves: Lesson Sets for Teaching Writing with Mentor Texts (Shubitz, 2016) teaches us about fiction lesson sets using what Shubitz calls “power craft moves,” of which Shubitz claims that any book we use as a mentor text must have at least six. Some of those power craft moves (Shubitz, 2016) I want to focus on include:

- Lead – “A good story needs a lead that hooks the reader. One way writers draw their readers into their stories is by comparing and contrasting emotions, which shows the complexity and oppositional pull of characters’ thoughts. This creates an immediate conflict, which sparks interest in what will happen” (p. 60-61).

- Dialogue – “Dialogue is one way writers add details to the plot and expand the relationships between characters while also moving the story forward” (p. 59).

- Ending – “A circular ending is one where the action of the story returns to the themes mentioned at the beginning. Essentially, the story ends where it began” (p. 60).

If we want students to internalize good story telling, they should become familiar with these power craft moves and learn to incorporate them into their own writing. In addition, teachers must find good mentor texts that highlight these strategies!

Six-Word Memoirs

Another great way to get students inspired in their writing is to try out six-word memoirs. Plenty of students have had the prompt to write a story about their lives—it’s a lot easier to write an entire story or even paragraph about one’s life—but how many will have summed it up in only six words? Having a limited word count places much more meaning on each one, and “every word is on trial” (Saunders & Smith, 2014, p. 602). With students, there are three goals of writing six-word memoirs that Saunders and Smith discuss in their article, “Every Word is on Trial: Six-Word Memoirs in the Classroom” (2014):

- Promote writing for the sake of expression,

- Reinforce tenets of the writing process, and

- Engage students in authentic use of technology, culminating in published work on the class blog.

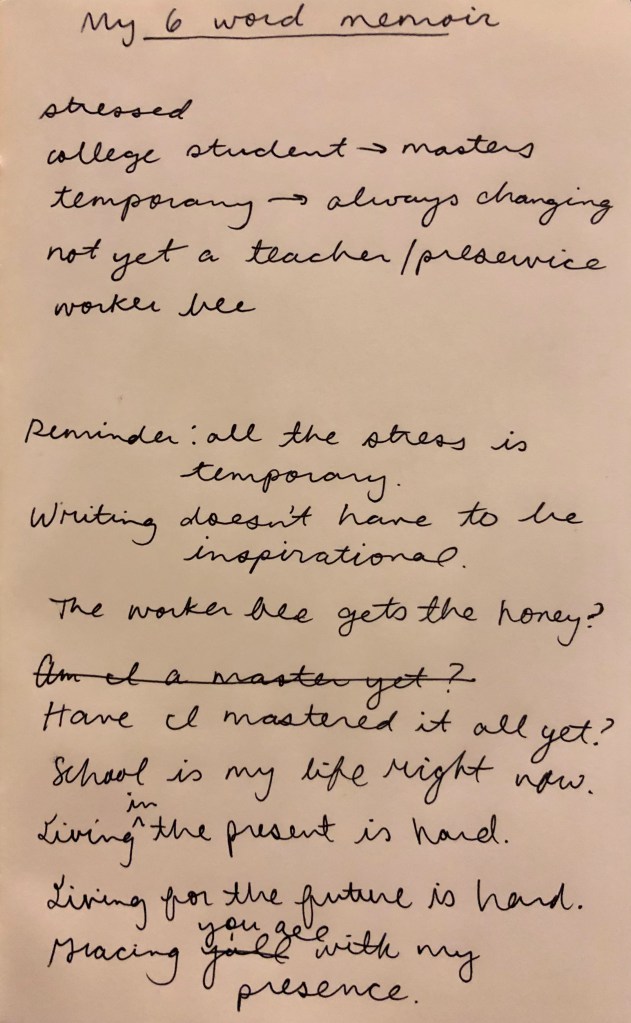

Saunders and Smith also say that employing six-word memoirs as a teaching tool should “help students define who they are as individuals” and help students “consider how these attributes affect the community around them” (p. 601). For an example of what drafting a six-word memoir might look like, take a look inside my Writer’s Notebook below:

My writing sample above shows exactly what students should see as they write in their own Writer’s Notebooks: notes at the top of things to maybe include, sections crossed out, and words inserted. When modeling writing, teachers must show students the messy process of writing—and it will get messy! I haven’t chosen my favorite sentence yet for my six-word memoir, but I think that’s okay. Writing is a process, and an author is not always truly happy with what they write, even when it is published! It is a wonderful thing to come back to a piece of writing and revise and improve upon it. Just listen to Jacqueline Woodson, author of brown girl dreaming (2016) and other books, talk about her own writing process and how revision is a natural stage of writing, in this video “Why I Write” (2018):

As I finish this post, I want to come back to the end of that essay I wrote as a college sophomore: “As I went along I found a direction in my writing, and began enjoying what I was writing.” If we lay out the foundational groundwork of writing strategies for students, I hope that they will develop this sense of authorship with their writing that I did with mine.

References Calkins, L. M. (2006). Revising leads: Learning from published writing. In A guide to the writing workshop, grades 3-5. Portsmouth, NH: Heinemann Dorfman, L. R., & Cappelli, R. (2007). Chapter 5: Creating powerful beginnings and satisfying endings. In In Mentor texts: Teaching writing through children's literature, K-6 (pp. 99-132). Portland, ME: Stenhouse Publishers. References National Council of Teachers of English. (2018, October 15). Why I write: 2018 National day on writing [Video]. Retrieved from https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=tE-dwp9bfeA&feature=youtu.be Saunders, J. M., & Smith, E. E. (2014). Every word is on trial: Six-word memoirs in the classroom. The Reading Teacher, 67(8), 600-605. doi:10.1002/trtr.1267 Shubitz, S. (2016). Craft moves: Lesson sets for teaching writing with mentor texts. Woodson, J. (2016). Brown Girl Dreaming (2nd ed.). New York, NY: Puffin Books.