I have always been a writer, ever since I was a child. My idea of a good time was writing a silly book with my best friend about M&Ms who could talk, and their interactions with humans. I would spend free time in my room writing in my SECRET-DO-NOT-ENTER diary. My favorite part of going to an art gallery is, to this day, viewing the pieces that feature text in some way. I gain a lot from words—and putting ideas down on paper. But I do not think I would be the writer I am had I not had excellent sources to serve as mentor texts.

Mentor texts are pieces of literature that serve to help writers use the writing skills they have not yet developed. In chapter 1 of Mentor Texts: Teaching Writing Through Children’s Literature, K-6 (2007) by Lynne R. Dorfman and Rose Cappelli, they claim that “Mentor texts serve to show, not just tell, students how to write well” (p. 4). As a child, I used mentor texts on my own to influence and better my writing, and I still do. Good writers learn from other writers: “Mentor texts help writers notice things about an author’s work that is not like anything they might have done before, and empower them to try something new” (p. 3). Good writers also begin as readers, and “writers should be introduced to mentor texts first as readers” (p. 5). Mentor texts should be well-loved and familiar, and this happens when writers learn to appreciate the characters, words, rhythm, story, and message of those well-loved and familiar stories from their own reading.

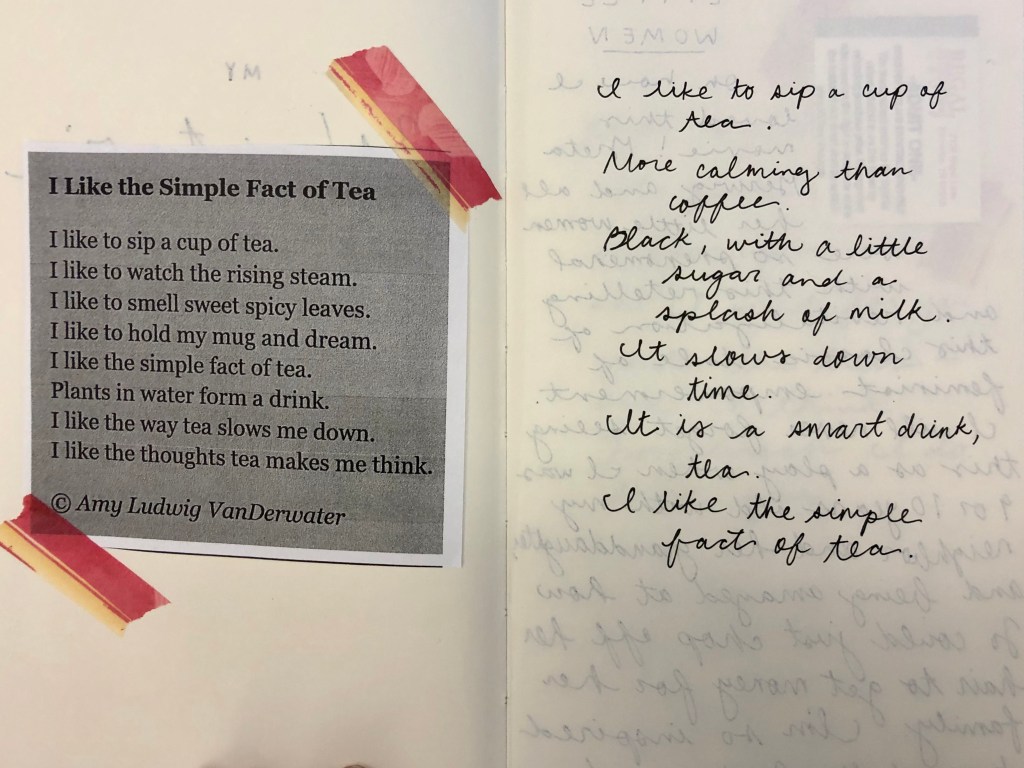

As teachers, we should strive to become writers ourselves, because as Dorfman and Cappelli say, “it would be difficult to teach someone how to swim if you didn’t do it yourself” (p. 9). Teachers should use mentor texts not only with students, but for their own writing as well. This helps us engage in the same challenges that our young writers will—and then develop the same problem-solving skills that we want them to use. Once we become familiar with those strategies through our own writing, we are more readily available for guiding our students in expanding their own. Students need a teacher who writes, who enjoys writing. In addition, as Dorfman and Cappelli point out, “Sometimes students need extended time to really try out a technique before it can become part of their repertoire of strategies” (p. 13). That’s where the Writer’s Notebook comes in handy.

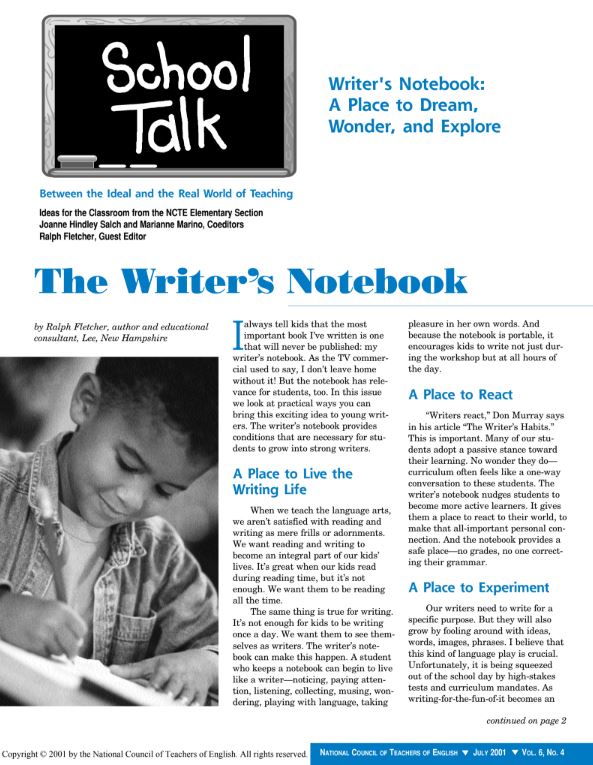

A Writer’s Notebook is a place to store ideas, enjoy language, experiment with new techniques, and develop as a writer. Ralph Fletcher wrote and edited an article in the journal School Talk titled “The Writer’s Notebook” (2001), in which he described the Writer’s Notebook as “a place to dream, wonder, and explore” (p. 1). It should be something a writer wants to write in, something they keep handy, and something they are using all hours of the day. As Fletcher writes,

Many of our students adopt a passive stance toward their learning. No wonder they do—curriculum often feels like a one-way conversation to these students. The writer’s notebook nudges students to become more active learners. It gives them a place to react to their world, to make that all-important personal connection. And the notebook provides a safe place—no grades, no one correcting their grammar.

This is a vital aspect of loving writing for our students. If students are forced into writing, particularly about topics they are uninterested in, they will learn to hate it. Developing skills through a Writer’s Notebook allows young writers to love writing. “Our writers need to write for a specific purpose. But they will also grow by fooling around with ideas, words, images, phrases” (p. 1).

I have just begun my own Writer’s Notebook and I have to say I already love it. I am so excited to continue my journey with it. The Writer’s Notebook has included several invitations for writers to use in their notebooks, which I hope to get a use out of in my own. Some of these include (p. 4-5):

- Three by Three – List three-word phrases for three minutes. Select a single word to designate a subject: summer, beach, school, etc. Get pencils ready—go! It doesn’t matter if the three-word phrases make sense.

- Write about Your Name – Write about your name in any way you choose: who you are named after, a name you were almost given, nicknames, how you feel about your name, etc.

- Capture What Is Important – Graham Salisbury offers this advice in Speaking of Journals: “Write…some little or big thing every day, and not stuff like ‘Today I went over to Jacky’s house and….’ No. That will be useless to you. Rather, write stuff like ‘Dad kissed me on the head today just before he left for work. He never kisses me like that, and I wonder what’s going on with him.’ Stuff like that—feelings, emotions. Good, meaty stuff.”

- Describe Your World – A writer’s eye takes in the surroundings with keen perception. Learning to “see” means stretching to use all five senses. Stake a claim on something—your desk, the classroom, the lunch-room, your bedroom. Don’t just describe what you see, but also include the sounds, smells, and feel of the place.

- Include Drawings and Sketches – Study something big (your backyard) or small (a daffodil just opening in spring). Make a drawing or sketch to capture the image. Then write in the empty space a description of what you see. Barbara Bash says, “I go out into an ecosystem and draw. By drawing it, I know it in a more intimate way. Even if it seems much too complicated to capture on the page, when I try to draw it I make an inner connection and understand it in a physical way.”

- Write to a Specific Audience – Think of something you’ve been wanting to say to someone and write it in your notebook in letter form. Write as if you are speaking directly to that person. You might even create a conversation and let the person speak back to you.

- Bits and Pieces – In Speaking of Journals, Jean Craighead George says, “It’s tough for kids to get started on journal keeping, so I suggest they bring back little things they pick up along the way—folders from a museum visit, a leaf, a dandelion—and paste them into a notebook. Then they can write their thoughts about them, what they saw and what they felt” (73).

Another excellent source of inspiration for writing in a Writer’s Notebook: Textbook Amy Krouse Rosenthal: Not Exactly a Memoir (2016) by Amy Krouse Rosenthal. I have barely even begun reading this not-exactly-a-memoir and yet I am already enthralled. Written as a “textbook” about the “textbook” (i.e., “classic”) Amy Krouse Rosenthal herself, this book includes quizzes to complete (by writing… in an actual, printed book!), cues to actually text the author, poems, pages with one sentence on them, and other narratives. This book provides its reader with many opportunities to utilize a mentor text.

LEXICO (by Oxford) defines serendipity as “the occurrence and development of events by chance in a happy or beneficial way.” Rosenthal takes a more creative and unique approach of defining through a numbered list of instances in which she has experienced serendipity (p. 24-33). My favorite of these examples is when Rosenthal describes having been at a book reading during which she decided to give away a ring of hers, has difficulty choosing which member of the audience to give said ring to, picks a woman who struck her the most of needing/wanting the ring, and tells her to pass the ring onto someone else on her birthday, April 29th… the same birthday as the woman to whom she gave it.

What I like most about Textbook so far is that it teaches writing techniques without the reader really thinking about it. It shows that writing doesn’t have to be this strict, properly formatted piece of text, but rather fun, sometimes unorganized, and creative process.

I must say, I have found all of the readings mentioned in this blog to be quite serendipitous-ly connected: through the use of “mentor texts” such as Textbook Amy Krouse Rosenthal, we can create in our “Writer’s Notebooks,” and in the process, become better writers.

References Dorfman, L. R., & Cappelli, R. (2007). Chapter 1: Reinventing the writer with mentor texts. In Mentor texts: Teaching writing through children's literature, K-6 (pp. 1-17). Portland, ME: Stenhouse Publishers. Fletcher, R., Salch, J. H., & Marino, M. (2001). The writer's notebook. School Talk, 6(4), 1-6. LEXICO. (n.d.). Definition of serendipity. Retrieved from https://www.lexico.com/en/definition/serendipity Rosenthal, A. K. (2016). Textbook Amy Krouse Rosenthal. New York, NY: Penguin Random House.

One thought on “The Serendipity of Mentor Texts & Beginning a Writer’s Notebook”